Hopi

Tewa Village and First Mesa

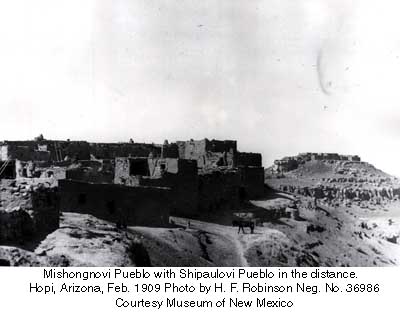

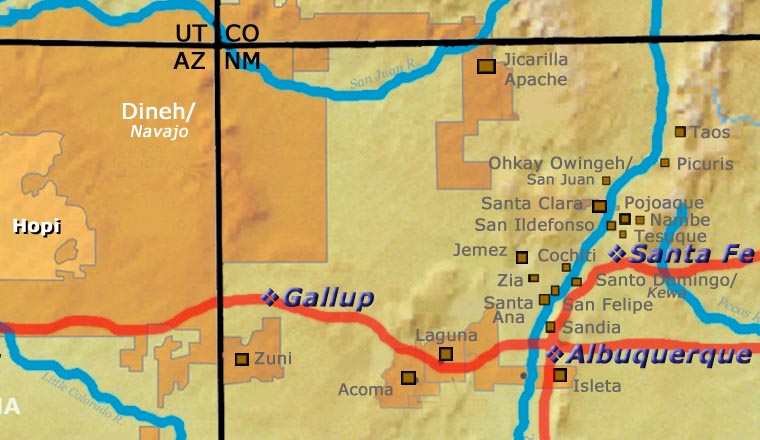

The Hopi people live in villages on or around three primary mesas in northeast Arizona. Some of these communities have been continuously occupied since the 12th century. Because they lived in isolation longer than any other pueblo group, the Hopis retain much of their traditional religion, lifestyle and language. That said, the Hopi mesas have also long been sanctuaries for other tribes during times of great drought or great hardship (such as those brought on by the Spanish in the early years of their colonization of New Mexico). As a result, the landscape around First Mesa is littered with the remains of villages once founded by people speaking Keresan, Towa, Tewa and other languages.

The Hopi pottery tradition is quite varied with roots traced as far away as vitrified ceramics found in the environs of Valdivia, Ecuador, and produced between 1200 and 1500 BC. Archaeologists excavating in the ruins around First Mesa found shards of pottery styles and painted designs also found in the Rio Salado region and among the ancient Sinagua settlements in the Wupatki, Tuzigoot, Walnut Canyon and Homolovi areas (all abandoned between about 950 and 1200 AD).

The area around Jeddito was occupied by Towa-speaking people from the Four Corners region beginning around 1275. The Jeddito area is where Jeddito yellow is found, the clay that made the pottery of Sikyátki so spectacular.

Beginning in the 1400's, Keres-speaking people arriving from the east began to build what became Awatovi, on Antelope Mesa between Jeddito and First Mesa. Sikyátki itself was also built by people from the east beginning in the early 1300's. At first Sikyátki was inhabited solely by the Kokop (Firewood) clan, then the Coyote clan came and grew to become the largest single clan in the village. Why the village was destroyed is shadowed in myth but Jesse Walter Fewkes (the first archaeologist to excavate in the Sikyátki area) felt the village was destroyed before the first Spanish visitor arrived in 1540. Oral history has it that Sikyátki and its people were wiped out but the clans that lived in the village have somehow continued to exist. Modern dating techniques have set the destruction of Sikyatki around 1625.

The Hopi Cultural Center

The ruins at Awatovi (on Antelope Mesa, east of Walpi and south of Keams Canyon) have yielded pottery shards in styles and with designs that were also prominent in the prehistoric village now known as Pottery Mound (in central New Mexico). Among the pot shards found at Pottery Mound are plain and decorated Hopi products, white clay products from the Acoma-Zuni area and red clay products from north-central New Mexico. Pottery Mound was abandoned about 100 years before the Spanish arrived in New Mexico in 1540.

It has been reported that many of the residents of Awatovi were Keres-speaking people from the Laguna-Acoma area (where Pottery Mound is) and, as such, were not as resistant as the Hopi themselves were to the Christianizing practices of the Spanish Franciscan monks when they came into the Hopi lands around 1609. As Awatovi was the only pueblo in the Hopi region to construct a Christian mission, most archaeologists attribute that to the reason why residents of Walpi and Old Oraibi destroyed the village and killed nearly all its residents in the winter of 1700-1701. However, at the time of that destruction, Awatovi was the largest and most populous pueblo in the Hopi mesas. It was also around 1690 that the people of Walpi were relocating from their old pueblo at the foot of First Mesa to their new location atop the southernmost finger of First Mesa, a move made for defensive reasons.

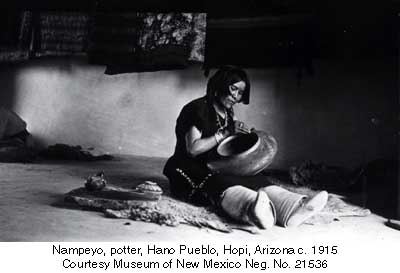

Southern Tewa warriors and their families (mostly from the Galisteo Basin and the area south of Santa Fe) began arriving in the area in 1696 and were steered to take up residence at the foot of First Mesa along the only route to the mesa top (in that location, the Tewas would be the first people to encounter incoming Spanish military - the people of Walpi felt they would make a good first line of defense should the Spanish attempt to reconquer them). The Tewas were also good at repulsing Ute, Paiute and Navajo raiders. After they won a decisive battle with Ute raiders they were allowed to build Tewa Village (also known as Hano) at the gap between the rocks on the trail up First Mesa. Some of the Tewa women were potters and in the ages-old way, they slowly shared what they knew with Hopi potters, and vice versa. That cross-pollination went on for years, and not just with pottery. Cross-cultural marriages happened, too, and today the people are known as Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Tewa, depending on their ancestry. And while Tewa Village is completely surrounded by the Hopi Reservation, many of the residents are fluent in Tewa, Hopi and English. Some are fluent in Spanish and Navajo, too. There is a tribal injunction against any Hopi speaking Tewa, they may understand what is being spoken in Tewa but they are not allowed to speak Tewa themselves.

During those same troubled times Towa-speaking people from Jemez Pueblo migrated to Hopi and Navajo territory (in the Jeddito Wash area) to escape the violence of the Spanish reconquest. They established familial ties that are still in place today (which may explain why Jeddito Wash is a Navajo Reservation area surrounded by the Hopi Reservation).

The village of Sichomovi on First Mesa was founded in the 1600's by members of the Wild Mustard Clan, Roadrunner Clan and others who'd come to the area from east of Santa Fe (Pecos Pueblo and the pueblos of the Galisteo Basin) via Zuni. They seem to have stopped at Zuni for a few years and assimilated somewhat. When they moved on to Hopi, there were quite a few Zunis among them, that's why the people of Walpi (and some from Zuni) refer to Sichomovi as a Zuni pueblo.

They arrived at Hopi around 1600 CE and became known as the Asa clan. They had traveled from the Abiquiu area through Santo Domingo, Acoma, Laguna and Zuni, picking up and dropping off people, technology and social practices along the way. Some settled at Awatovi while others continued to Coyote Spring (under the gap at First Mesa). They built a new pueblo where Hano now stands (it was known as Hano back then, too). A few years later drought and disease caused them to relocate again.

They went east to the Navajo settlements around Canyon de Chelly and most stayed there several decades before an argument with the Navajo caused some to either return to First Mesa or travel east to the Rio Grande Pueblos. The descendants of those who intermarried with the Navajo stayed with the Navajo and are now a numerous clan known as Kinaani (High-standing house).

Those who returned to First Mesa found Hano occupied by the newly arrived Southern Tewa. The Asa were given a strip of land on the east edge of the mesa to build on but soon after, many of them moved to Sichomovi and merged with clans there.

Around 1800 a period of severe drought caused many Hopis to migrate to Zuni territory and once the drought had broken, most returned to their ancestral lands. While at Zuni many Hopi potters picked up the Zuni method of white-slipping their pottery and continued to produce white ware after returning to Hopi. However, their quality wasn't nearly as good as that of Hopi pottery produced pre-1700.

The quality, styles and designs of Sikyátki had lived on in Awatovi pottery, although the potters of Awatovi were also enamored of using a white slip on top of the Jeddito clay base. The potters of Awatovi also introduced some new designs (the "Awatovi star" being one) but after the village was destroyed, very little of their knowledge and practice passed on. Hopi ceramics entered a virtual Dark Age for almost 200 years.

By the mid-1800's the Hopi pottery tradition had been almost completely abandoned, its utilitarian purposes being taken over by cheap enamelware brought in by Anglo traders. Hopi pottery production sputtered along until the late 1800's when one woman, Nampeyo of Hano, almost single-handedly revived it. Nampeyo lived in Tewa Village on First Mesa and was inspired by pot shards found among the nearby ruins of the ancient village of Sikyátki. Today credit is given to Nampeyo for fully reviving the Sikyátki style. She was so good that Jesse Walter Fewkes, the first archaeologist to formally excavate Sikyátki, was concerned that her creations would shortly become confused with those made hundreds of years previously.

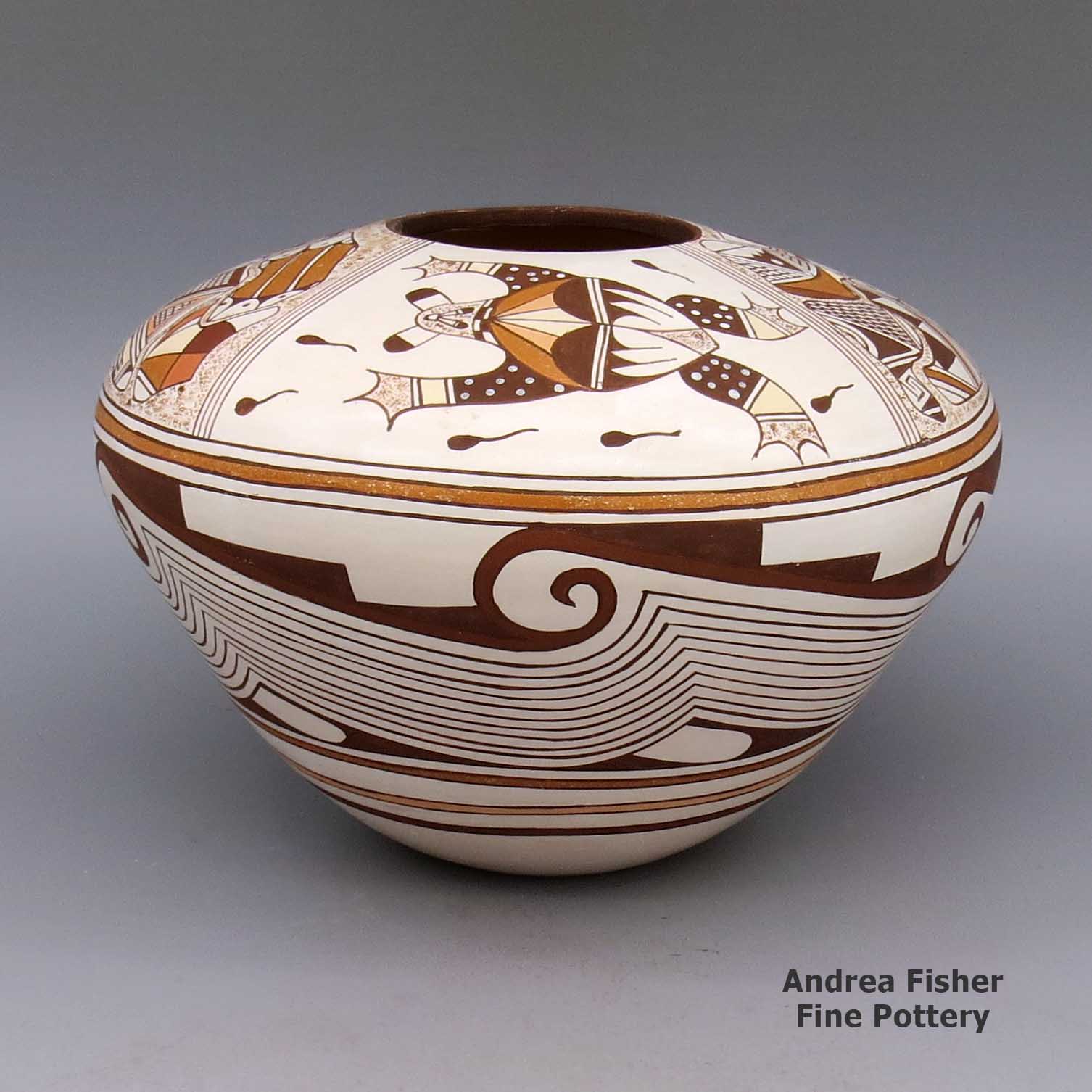

Sikyátki pottery shapes are very distinctive: flattened jars with wide shoulders; low, open bowls decorated inside; seed jars with small openings and flat tops; painting methods of splattering and stippling and very distinctive designs. The Sikyátki style originally evolved when Keres and Towa-speaking potters from New Mexico got together with Water Clan potters from the Hohokam areas of southern Arizona and northern Mexico and they began working with clays found in the Jeddito area. Over the years other clans came to the area and made their own contributions to what we now know as "Sikyátki Polychrome." Accoding to Jesse Walter Fewkes, that merging of styles, techniques and designs created some of the finest ceramics ever produced in prehistoric North America.

Today's Hopi pottery tends to be a white, yellow, orange or buff colored background decorated with designs in red and black mineral paints. Painted designs tend to fill the entire space, often with an asymmetrical and symmetrical design. Most of the symbology painted on Hopi pottery is themed with "bird elements:" eagle tails, feathers, bird wings and migration patterns. Many Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Tewa potters are members of the Corn Clan and their annual religious cycle revolves around the seasons of corn. The vast majority of today's Hopi pottery shapes and the designs painted on them are obvious descendants of the work of Sikyátki and Awatovi potters.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Micaceous Clay Pottery

Angie Yazzie

Taos

Christine McHorse

Navajo

Clarence Cruz

San Juan/Ohkay Owingeh

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

As we understand it, potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have said there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker, heavier and rougher on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and conducts heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner and have a smoother surface. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

While all micaceous clay from the area of Taos turns golden when fired, it can also be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and San Juan use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home in the Jemez Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Navajo potter who married into Taos Pueblo, uses various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asks of her in the flow of her creating.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. There are some who have learned to successfully paint on a micaceous surface. The undecorated sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of simple shapes is a real testament to the artistry of the micaceous potter.

100 West San Francisco Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved

Naha-Navasie Family Tree

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Paqua Naha aka 1st Frogwoman (c. 1890-1955)

- Joy Navasie aka 2nd Frogwoman (1919-2012) & Perry Navasie

- Grace Navasie Lomaquahu (1953-) & Olson Lomaquahu

- Leona Navasie (1939-)

- Loretta Navasie Koshiway (1948-)

- John Biggs (adopted, 1970-)

- Charles Navasie (1965-)

- Lana Yvonne David (1971-)

- Marianne Navasie (1951-2007) & Harrison Jim

- Donna Navasie Robertson (1972-)

- Maynard Navasie (1945-) & Veronica Navasie (1945-2003)

- Bill Navasie (1969-)

- Roy Navasie (1970-)

- Helen Naha aka Feather Woman (1922-1993) & Archie Naha (d. 1993)

- Burel Naha (1944-)

- Rainy Naha (1949-)

- Amber Naha (1991-)

- Tyra Naha (Tewawina) (1973-)

- Sylvia Naha Humphrey (1951-1999) Student of Helen, Rainy and Sylvia:

- Nona Naha (1958-2021) & Terry Naha

- Terran Naha

- Helen Naha & Hugh Sequi

- Cynthia Sequi Komalestewa (1954-)

- Miltona Naha (1962-)

- Agnes Navasie (Joy Navasie's mother-in-law)

- Eunice Fawn Navasie (c. 1920-1992) and Joel Nahsonhoya

- Dawn Navasie (1961-)

- Dolly Joe White Swann Navasie (1964-)

- Fawn Little Fawn Navasie (1959-)

- Student: Gloria Mahle

- Justin Navasie & Pauline Setalla (1930-)

- Agnes Nahsonhoya (1956-)

- Derek Nahsonhoya

- Dee Setalla (1963-)

- Gwen Setalla (1964-)

- Karen Namoki (1960-)

- Stetson Setalla (1962-)

- Agnes Nahsonhoya (1956-)

Some of the above info is drawn from Hopi-Tewa Pottery: 500 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 1998, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies. Other info is derived from personal contacts with family members plus interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examinations of the data found.

(505) 986-1234 - www.andreafisherpottery.com - All Rights Reserved